Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report shows that the reef is in serious trouble

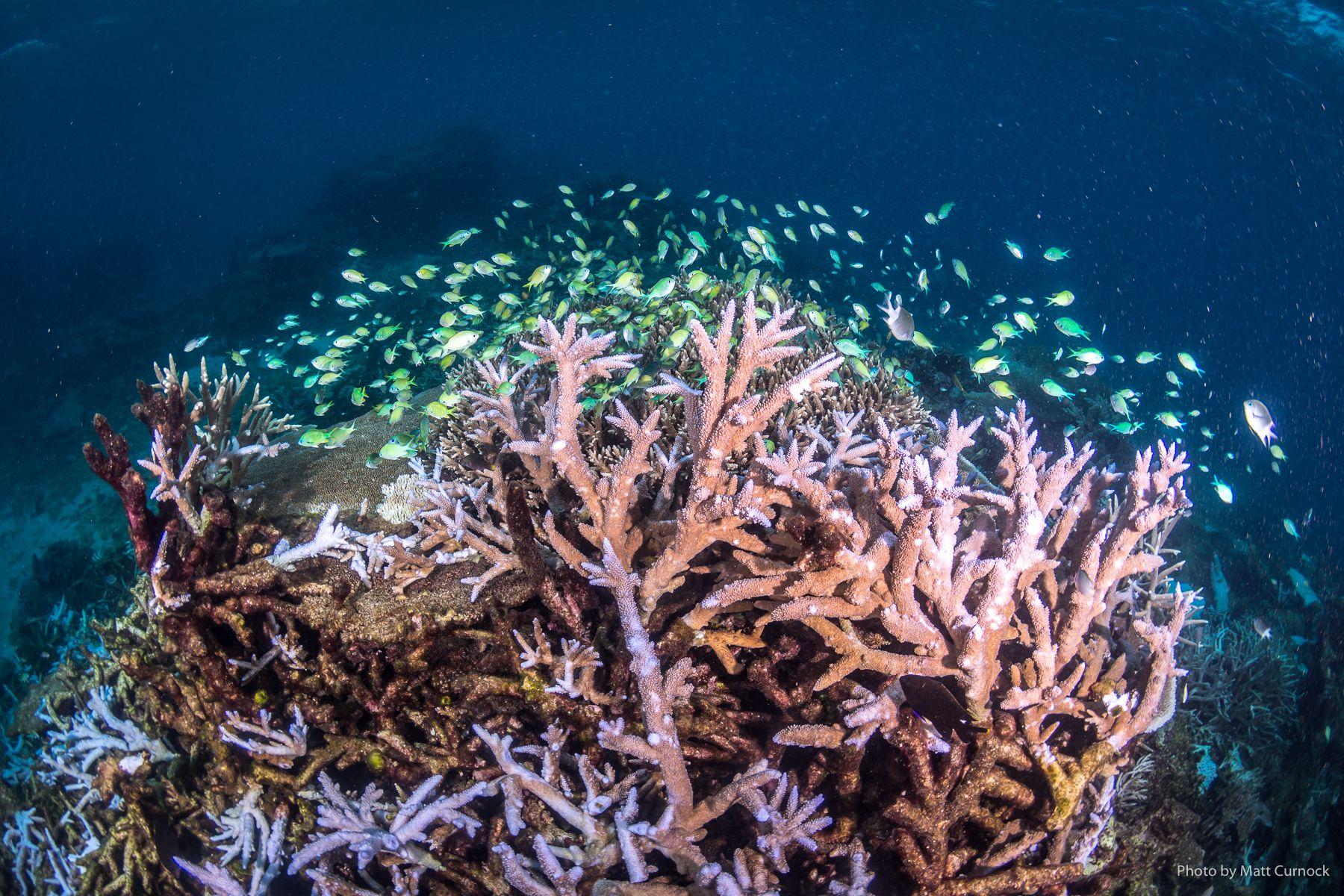

John Brewer Reef, off Townsville in February 2024, showing impacts from Tropical Cyclone Kirrily and coral bleaching. Image: Matt Curnock

Media Release

26 August 2024

The latest 5-yearly report for the outlook of the Great Barrier Reef shows that the reef is in major long-term decline despite the modest investments that have been made.

The 2024 Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report has just been released by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). The last outlook report was released in 2019.

The Biodiversity Council says that:

- The comprehensive report is a major scientific effort and rigorously synthesises a huge amount of data. The quality of the report is a testament to the independence of GBRMPA and Australia’s world leading reef scientists.

- The substance of the report shows that the reef is in major long-term decline despite the modest investments that have been made.

- The commentary and key findings released with the report gloss over the gravity of the situation. The Great Barrier Reef is in very serious trouble.

- Climate change is the biggest threat to the reef.

- Catchment restoration activities that reduce sediment flowing to the reef will aid the health of the reef but cannot match the scale of destruction occurring due to marine heatwaves caused by climate change.

- Reversing declines of long-lived species like sea turtles, sharks, dugongs and seabirds requires decades of investment. The Queensland and Federal Government investments in management, protection, research, and monitoring, will need to be larger and more sustained if we are to recover these iconic species groups.

- We all have a role to play to save the reef by taking personal climate action.

Biodiversity Council member and coastal ecosystems expert Professor Catherine Lovelock from the University of Queensland said:

“The upbeat tone of the key findings contrast with the troubling detail held within the report.

“Climate change poses the greatest threat to the Great Barrier Reef. We must keep that front of mind and call for greater climate action.

“Sediment is another major threat to corals and seagrass. Sediment has not been declining and there is a great need to increase catchment restoration, including a focus on stream bank vegetation and wetlands to reduce the impact of sediment on the reef.

“There is an opportunity for new investments in the repair of streamside vegetation and wetlands by Indigenous custodians. This would benefit both marine biodiversity and terrestrial biodiversity.

“The Outlook Report provides all the evidence needed to follow this strategy. Let’s cut through the governance quagmire and get to it.”

Biodiversity Lead Councillor and marine turtle expert Associate Professor Nicki Mitchell from the University of Western Australia Oceans Institute said:

“The report paints a grim picture for Queensland’s sea turtle populations.

“Climate change is already having a direct impact on nest success and sex ratios, but poor body condition due to food shortages reduces the frequency that females breed, which compounds the impact.

“We can’t be complacent when populations start to decline. Cumulative impacts become much more serious when populations become very small.”

Biodiversity Councillor Professor Graeme Cumming from the University of Western Australia Oceans Institute said:

“It is very sad to see the large declines being observed seabird populations. The Great Barrier Reef is extremely important for a wide range of seabirds that often breed on small islands and feed in the surrounding ocean.

“Very little is yet known about how ocean warming is affecting the availability of food for seabirds.

“Although avian influenza is having an enormous toll on seabirds overseas and will arrive in Australia, likely in the near future, the report does not consider how avian influenza or other avian diseases could impact seabird populations that are already struggling.

“If the Australian Government is serious about conserving the unique seabird fauna of the Great Barrier Reef, additional funding for basic research on seabird population dynamics, movements, diseases, and foraging is required. This information will be critical for developing and implementing deliberate management strategies."

Biodiversity Councillor Dr Angela Dean from The University of Queensland is a conservation social scientist working with a range of government and non-government partners on reef stewardship programs.

“The Great Barrier Reef is part of our Australian identity, whether we live in Cairns or Tasmania we all care about what happens to the reef and wherever we live, we can all make a difference.

“Climate change is the number one threat to the reef so we need to do everything we can to decarbonise.

“The first way we can help is by taking personal climate action, for example by switching off lights we aren’t using, installing solar, and switching some of our car trips to public transport or bicycle.

“The second way every Australian can help is through civic action. We can contact our political representatives and governments and let them know that we want more action to decarbonise Australia to protect the reef and our diplomats need to be pushing other countries to do the same.”

The Biodiversity Council was founded by 11 Australian universities and draws together leading Australian experts, including reef and marine biodiversity experts, to promote evidence-based solutions to Australia’s biodiversity crisis.