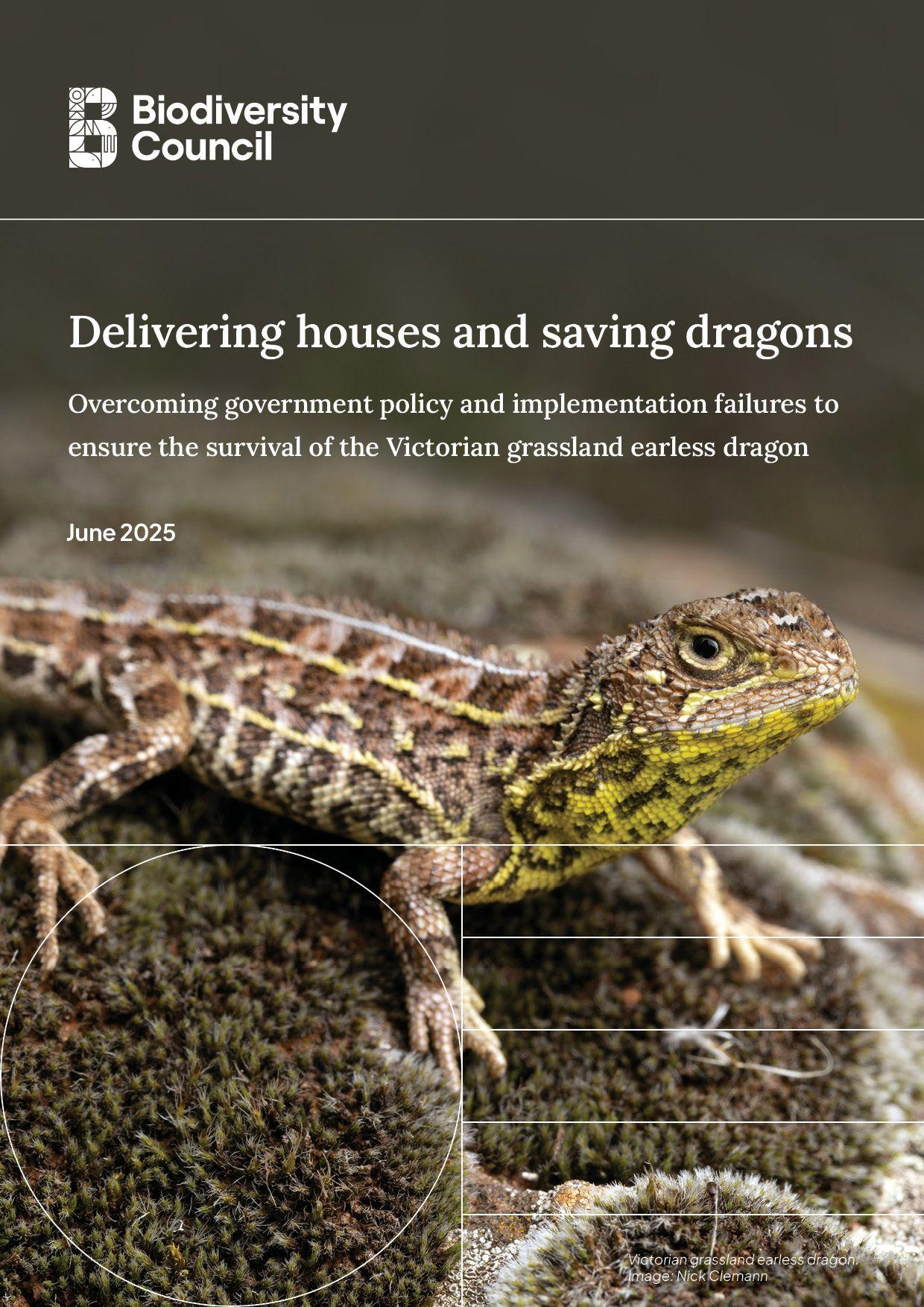

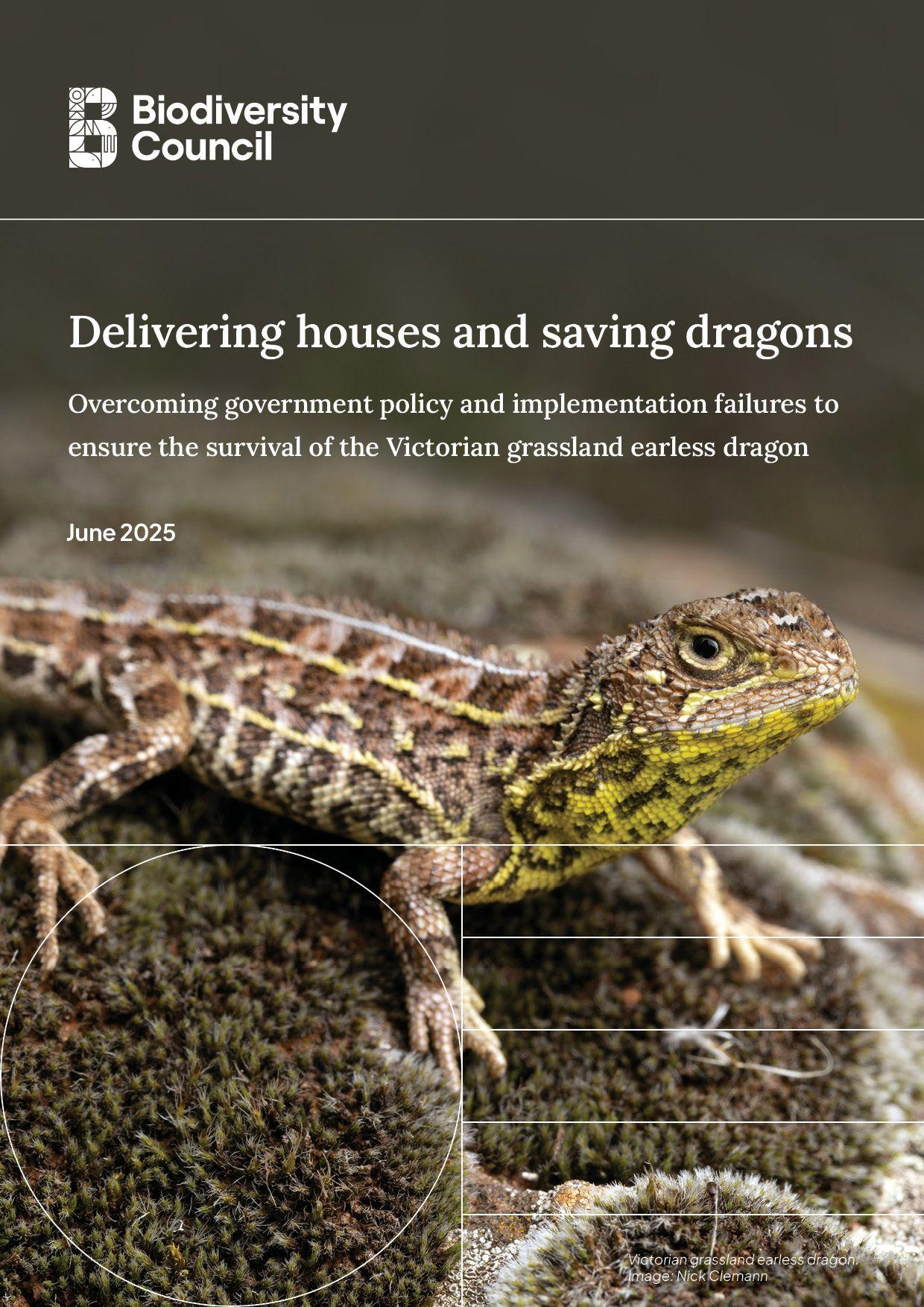

Victorian grassland earless dragon. Image: Peter Robertson

Delivering houses and saving dragons: Overcoming government policy and implementation failures to ensure the survival of the Victorian grassland earless dragon

Report

12 June 2025

Executive Summary

The Victorian grassland earless dragon (Tympanocryptis pinguicolla) is a fascinating small lizard that uses spider burrows for shelter. In this report, ‘the dragon’ refers to this species.

The dragon is restricted to native grasslands between Melbourne and Geelong in a region that is being rapidly developed. It is known from just one wild location, on private grazing land that is slated for development, putting it at grave risk.

Without immediate evidence-based action, the dragon could become extinct in the wild. This outcome is not inevitable, and the options are not simply a binary choice of building housing or saving the dragon. It is entirely possible for the Australian and Victorian governments to protect the dragon while delivering more houses for Australians.

This report explains how current efforts to guide Melbourne’s growth are failing the dragon and its grassland habitat, and outlines a pathway to:

- prevent its extinction,

- protect the grassland ecosystem, and

- support continued urban development.

The report contains detailed recommendations, for the Australian and Victorian Governments, chief among these is the urgent need to:

- Protect the wild population through land purchase and conservation management;

- Conduct targeted surveys across suitable habitat, regardless of land tenure;

- Complete the Western Grassland and Grassy Eucalypt Woodland Reserves, with a review of boundaries to ensure they capture sites needed for the dragon’s recovery

- Establish new wild populations using captive-bred dragons from Zoos Victoria;

- Better involve species experts—the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon Recovery Team—in decisions affecting the species.

The dragon’s rediscovery is a rare opportunity to prevent extinction. Its fate is a test of how seriously governments take sustainability and environmental law. We must not squander this chance.

While this report examines how to protect the dragon during the roll out of new housing areas on Melbourne’s western fringe, that does not mean the Biodiversity Council endorses urban sprawl as a sustainable or effective solution to providing more housing. We recommend the Victorian Government implement the recommendations of Infrastructure Victoria, who urge a focus on ‘compact cities’ rather than urban sprawl. Their analysis found this would be better for the environment and for people and would save the economy $43 billion by 2056.

Summary of key findings

Species and ecosystems at high risk of extinction

The dragon’s fate reflects the drastic loss of its grassland habitat in Victoria, of which only 2% remains. The dragon is considered Australia’s most imperilled reptile. For over 50 years, there were no verified sightings. However, happily, in 2023, it was rediscovered at a single location just west of Melbourne.

Both the grassland and the dragon are listed as Critically Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The grasslands also contain ten other nationally threatened species and ecosystems.

The Australian Government is legally obligated to protect nationally threatened species and ecosystems under the EPBC Act. The Australian Government has also committed to preventing extinctions.

With only one known population. Any additional site where the dragon is detected must be protected and managed for the conservation of the species.

Delivering development while meeting environmental protection obligations

The region is undergoing rapid transformation under Melbourne’s urban expansion, and the dragon’s only known wild population, and other grassland areas where it may occur, have been slated for urban development, placing it at grave risk.

Under the EPBC Act, developments with the potential to significantly impact EPBC Act listed threatened species or ecosystems require Commonwealth assessment and approval. The intention of the approval process is to identify development pathways that avoid and then mitigate impacts to threatened species and ecosystems as much as possible, and to finally offset remaining impacts where suitable. If remaining impacts are likely to be significant, the Australian Government may refuse the project.

To streamline assessments in growth areas, the Australian and Victorian Governments established the Melbourne Strategic Assessment (MSA), a regional approval under section 146 of the EPBC Act. The MSA aimed to meet federal environmental protection obligations through upfront strategic planning, replacing project-by-project assessments. The Victorian Government committed to avoiding, mitigating, and offsetting impacts to threatened species and ecosystems in the MSA area.

If well designed and implemented, the MSA had the potential to deliver positive environmental outcomes, including securing the long-term survival of the region’s threatened species, such as the dragon.

When the MSA was endorsed in 2010, the dragon had not been recorded in Victoria for more than 40 years. While that complicated planning, the requirement to survey for the species and respond to new information remained.

Crucially, while in 2010 it was believed that the dragon also occurred in New South Wales, in 2019 research found that the Victorian dragon was a different species, and is likely to suffer the greatest habitat loss of any species under the MSA. In 2023 it was discovered at one site. This is the only known wild population but it may also occur at other sites.

Some newer urban growth areas fall outside the MSA and still require project-level EPBC approvals if the project is likely to have significant impacts on EPBC Act listed threatened species or ecosystems. Regardless of location, the Australian Government is responsible for ensuring all developments meet their legal obligations to ensure the future of threatened species and ecosystems.

Major failures in development processes

In 2020, the Victorian Auditor General found major failings in the delivery of the MSA and these have not yet been addressed. Failures in the design and the implementation by the Victorian Government mean that the MSA is not meeting its objectives or legal obligations.

The MSA contained a requirement to survey for the dragon which did not occur. Populations that exist but are not known (and hence not protected) face a perilous future. Targeted surveys for the dragon at potential sites, regardless of tenure, remain an urgent priority.

Conservation reserves promised under the MSA in 2010—most notably the 15,000-hectare Western Grassland Reserve and 1,200-hectare Grassy Eucalypt Woodland Reserve—remain largely unacquired, even though they had a deadline to be secured by 2020.

The failure to rapidly acquire and protect the land earmarked for reserves has led to major degradation of the values that the MSA committed to protect and is undermining the capacity of the reserves to deliver biodiversity benefits sufficient to serve as a credible offset.

The boundaries of the proposed reserve also need to be reviewed to capture dragon rediscovery and potential reintroduction sites, in light of significant new information.

Given how little is left, it is important to protect areas with potentially suitable dragon habitat even if they have not yet been detected there. Dragons may still be at these sites and they will be needed to establish new populations using animals bred at the Melbourne Zoo conservation breeding program.

The rediscovery of the dragon in 2023, triggered additional legally required actions under the MSA, however most of these have not occurred. Survey guidelines have recently been released by the Australian Government, but conducting targeted surveys for the dragon across all potentially suitable habitats and developing guidelines for the dragon’s protection and management if detected remain outstanding.

Despite these basic environmental protection failures, habitat destruction to make way for development continues in areas that may contain undetected dragon populations.

Utilise recovery team experts

Given the dragon’s cryptic nature and extreme imperilment, all actions must be guided by the best available knowledge and expertise.

To recover this species it is very important to ensure that experts with the most knowledge and experience with this species are engaged in decisions that affect the conservation of the species. The situation we are in now may have been avoided if species-experts had been more closely involved in planning processes, including surveys for the species and identification of conservation areas.

The Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon Recovery Team—comprising herpetologists and representatives from Zoos Victoria, the Victorian and Commonwealth Governments, Museums Victoria and first peoples —is leading conservation efforts and should be central to all work on the species.

The EPBC Act created a pivotal role for recovery teams in advising on complex management issues and coordinating recovery actions for threatened species. Recovery teams should be central to decision-making for all threatened species within the region.

Given the dragon’s rarity, even expert consultants are likely to lack experience with the species. New federal survey guidelines are welcome, but the recovery team should also review consultants’ survey results and interpretations rather than just be consulted on survey prescriptions.

One positive development for survey efforts is the recent successful trialling of detector dogs, trained to smell out the otherwise highly cryptic dragons. Such canine accomplices may greatly increase future survey efficiency and likelihood of success.

Some areas of grassland earmarked for the Western Grassland Reserve have been destroyed by being tilled for cropping (as shown here). Image: USGS Earth Explorer

Summary of recommendations

Urgent action is required. To avoid extinction of the Victorian grassland earless dragon in the wild, governments must immediately work to implement their commitments under the EPBC Act, Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (Vic) and the MSA and take evidence-based steps to safeguard this species and its habitat.

Use the species experts - All activities related to the dragon must be done in collaboration with the recovery team, including targeted surveys, management of wild populations and the development of guidelines.

Key recommendations for the Australian Government

Secure the species in the wild – Urgently provide resources for the recovery team to undertake research trials to establish five new wild populations of the dragon in the short-term, using animals from the Zoos Victoria conservation breeding program, with a long-term target of establishing 12-15 self-sustaining wild populations.

Audit the MSA – Audit the Victorian Government’s compliance with its 2010 MSA approval. Identify gaps and negotiate a plan with the Victorian Government to meet them. The audit must address commitments to adequately survey for the dragon, protect it in the wild and establish and appropriately manage reserves. Make the findings publicly available in annual reviews until all commitments are delivered.

Audit areas outside the MSA - Audit the performance of development processes, approvals and planning frameworks across regions where the dragon may occur that are outside of the MSA against whether they are meeting the obligations of the EPBC Act in protecting the dragon and other threatened species and ecosystems. This must include within the Bacchus Marsh and Geelong Growth Areas, and areas outside of these that are modelled habitat for the dragon. Make the findings publicly available.

Develop industry guidelines for avoiding, assessing and mitigating impacts on the Victorian grassland earless dragon.

Ensure compliance with comprehensive pre-development survey requirements in all areas where potential habitat will be destroyed outside the MSA, even if habitat is considered low value by consultants. Supply results to the recovery team for interpretation and review.

Use the federal Saving Bushland Program to support the immediate purchase and management of the single property where the dragon has been discovered in the wild. If the dragon is confirmed on other private properties, they should also be purchased.

Support research to refine detection methods.

Key recommendations for the Victorian Government

Protect the wild population - Urgently purchase the property where the only known wild dragon population occurs and ensure that it is secured in perpetuity and appropriately managed by a suitable authority e.g. Trust for Nature or other proven entities e.g. Bush Heritage. Protect every site where dragons are are detected.

Secure sites needed for dragon recovery - Acquire and protect additional sites containing suitable dragon habitat, to support dragon recovery, as determined neccessary by the recovery team.

Survey for the dragon – Support the recovery team to urgently conduct targeted surveys across all potentially suitable locations, regardless of land tenure.

Ensure compliance with comprehensive pre-development survey requirements in all areas where potential habitat will be destroyed within the MSA, even if considered low ecological value by consultants. Supply results to the recovery team for interpretation and review.

Secure the species in the wild – Urgently provide resources for the recovery team to undertake research trials to establish five new wild populations of the dragon in the short-term, using animals from the Zoos Victoria conservation breeding program, with a long-term target of establishing 12-15 self-sustaining wild populations.

Ensure high biodiversity value sites are captured in conservation reserves - Urgently review the boundaries of the Western Grassland Reserve to ensure it captures the most ecologically valuable remaining grassland remnants, the dragon rediscovery site, and an adequate number of sites containing suitable dragon habitat for dragon recovery, determined by the recovery team.

Establish the Western Grassland and Grassy Eucalypt Woodland Reserves - Urgently complete the acquisition and management of these reserves by 2027 reflecting the revised boundaries.

Adapt to significant new knowledge about the dragon as it emerges, in collaboration with the recovery team. For example, review reserve boundaries if a second wild remnant population is discovered.

Make a critical habitat determination under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 for the grasslands, followed by a habitat conservation order to prohibit any development or land use that would impact the grasslands identified for the reserves.

We urge the Australian and Victorian Governments to act swiftly on these recommendations to meet their legal and moral duty to prevent the dragon’s extinction and deliver lasting environmental outcomes alongside development.

Download the report for more detailed analysis of issues and recommendations.

Cite this report as: Biodiversity Council (2025). Delivering houses and saving dragons: Overcoming government policy and implementation failures to ensure the survival of the Victorian grassland earless dragon. May 2025. Report. Melbourne, Australia.